Expert Spotlight: 5 Questions with David Wallinga, NRDC

There’s been a great deal of progress in reducing antibiotic use in the poultry industry and now public health experts are urging the beef and pork sectors to follow suit. Enter, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a non-profit that has worked since 1970 to ensure the rights of all people to clean air, clean water, and healthy communities. NRDC has recently released a new issue brief, Better Bacon: Why It’s High Time the U.S. Pork Industry Stopped Pigging Out on Antibiotics. We talked to NRDC’s Senior Health Officer Dr. David Wallinga to find out what inspired this new report.

1. We LOVE bacon. Most people we encounter love bacon and some ask “what’s bacon have to do with antibiotic resistance? ”Can you tell our readers why they should be concerned?

People love bacon, but right now the way it’s being produced is weakening the ability of antibiotics to fight off infections when people get sick—and there’s absolutely no need for that. We’re saying, you should be able to have your bacon and eat it too!

There’s a growing global epidemic of infections from superbugs that are hard or impossible to treat with antibiotics because overuse of the drugs is making bacteria more resistant to them. Already, at least 2 million people in the U.S. are getting sick from drug-resistant infections, and 23,000 are dying, every single year, according to the U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

2. Experts around the world, including the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urge an end to unnecessary uses of antibiotics in human medicine and food animal production to help reduce antibiotic resistance and protect public health. What do you think the pork industry should do to help address antibiotic resistance?

With so many of these precious drugs going to pigs that aren’t even sick, we’ve got to address this problem in the pork industry in order to keep antibiotics working for when sick people and animals need them.

The U.S. pork industry has to become a leader, not a laggard, in reducing its own use of antibiotics. Any reduction in use of antibiotics will help lessen the selection for drug-resistant superbugs to develop and then spread from farms to human populations.

The thriving pork industries in Denmark and the Netherlands have ended routine use of medically important antibiotics, on route to reducing that use by 27% and 57%, respectively, over less than a decade. Our Better Bacon report shows pig producers in those countries replaced those antibiotics with relatively straightforward changes to how they raise pigs, like more frequent housecleaning, improved ventilation and less cramped quarters. They still produce hogs at an industrial scale -- as is done in the U.S., they just do it differently.

3. Data on the use of antibiotics in livestock production in the U.S. is relatively scarce. It’s interesting that your Issue Brief includes a breakdown of medically important antibiotics sold for use in the U.S. for pig production, other livestock production and human medicine. Tell us more about these numbers, how you determined them and what they mean.

For the Better Bacon report, we were determined to use available data to tell American consumers a clear story about why, how and how many antibiotics are being used in the U.S. pork sector. In contrast to Europe, as Maryn McKenna tells us in WIRED, “the information we‘re allowed to have about how antibiotics are used in U.S. animals is limited, incomplete, and hostage to commercial interests.”

So, how exactly did we tell our story? Basically, we did nothing more than what the USDA and FDA could and should be doing on behalf of the public they are supposed to serve. We found bits of data that already exist in disparate places and just brought it together. The FDA, for example, already reports annually on sales of medically important antibiotics across all animal sectors. In December, the FDA reported for the first time sales by animal species. When it issues these reports, however, the FDA either can’t or won’t also report on the sales of these same classes of antibiotics for use in human medicine. Those data can be accessed by anyone paying a hefty fee to the private company – called Quintiles IMS, formerly IMS Health -- that collects these data from individual drug makers and then repackages it for sale. Presumably, the FDA either can’t or won’t pay the fee.

We found the latest 2015 human drug sales figure on the website of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy, where the FDA also could have found it. In creating our pie chart, we make the highly defensible assumption that human sales of these drugs in 2016 aren’t likely to vary much from the 2015 figures.

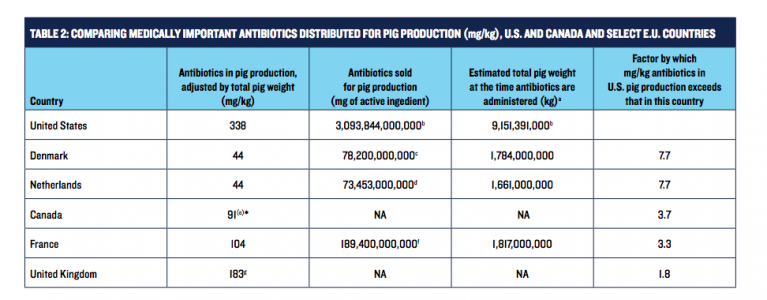

4. How does antibiotic use in food animal production (including pig production) in the U.S. compare to other countries like Denmark and the Netherlands?

The U.S. pork industry uses almost eight times more medically important drugs per kilogram of pig produced than do Denmark and Netherlands, which produce pigs at a similar industrial scale.

Like in the U.S., the pork industries in the Netherlands and Denmark are profitable, growing and export-oriented. Combined, the pork industries in these two countries are about the size of Iowa’s, which is the largest pork-producing state in the U.S. And they are among the world's biggest pork exporters.

Until recently, Denmark and the Netherlands also were heavy antibiotic users. But in less than a decade, as I mentioned above, they’ve cut antibiotics use in pig production by 27 percent and 57 percent respectively. Both countries have replaced routine antibiotics use with relatively straightforward changes—including more frequent housecleaning, improved ventilation and less cramped living quarters.

With so much in common and so much progress made in such a short time period—Denmark and the Netherlands show that responsible antibiotic use in the pork industry is achievable, scalable and profitable. And they set a model for the U.S. industry to follow. You can learn more about the success of these countries in this report: Combating Antibiotic Resistance: A Policy Roadmap to Reduce Use of Medically Important Antibiotics in Livestock.

5.The CDC has noted (as well as countless research studies) that the widespread use of antibiotics on industrial farms creates a microbial environment on and around those farms that serves as a reservoir of antibiotic resistance. How does this then impact human health?

We talk about U.S. pig farms as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance, as well. In short, the longstanding and enormous use of medically important antibiotics in these operations creates conditions ideal for the development and spread of drug-resistant bacteria from these farms to the human population as a whole. There’s evidence that spread happens through several possible routes. First, resistant bacteria in a pig’s gut often contaminate pig meat that ends up in the supermarket. When home cooks handle raw pork chops, for example, it could lead to these bacteria taking up residence in their own bodies, or those of their family members.

Second, resistant bacteria in pigs can infect the farmers and farmworkers handling those pigs, who can in turn pass those bacteria to their family members and neighbors.

Third, pig manure is loaded with drug-resistant genes and bacteria that can spread in the air via dust blown downwind of pig farms, and via water after rain or irrigation runs off farms or fields where manure is spread into streams, rivers, and other nearby waters.

Little wonder, then, that several studies now document higher risks for drug-resistant infections among farmers and others who work with pigs, veterinarians, and people living in communities adjacent to pig farms. This also means using these drugs more responsibly is especially urgent for the people who work in the industry.

6.Bonus question! What can consumers and policymakers do to help encourage the reduction of antibiotic use in food animal production and human medicine?

Consumers have been a driving force in demanding that U.S. meat producers do more to curb their overuse of medically important antibiotics. They should keep voting with their wallets and urging their favorite restaurants and brands to clean up their act—they’re increasingly listening, and that has powerful ripple effects.

For example, NRDC estimates that more than 50 percent of the U.S. chicken industry is now either under an antibiotics stewardship commitment or is already using responsible practices. This progress has been driven by major chicken producers such as Perdue, Tyson and Foster Farms, as well as giants of the fast food industry—such as McDonald’s, Subway and KFC.

Pork is another story. Some American companies are starting to tackle the problem: Niman Ranch, Applegate and Meyer Natural Pork are all growing U.S. companies that sell responsibly raised pork. Chipotle and Panera – leaders in the restaurant industry – do not allow antibiotics to be used in their pork supplies. Even mainstream producers Tyson and Smithfield have started niche lines without routine antibiotic use, though these product lines represent a tiny fraction of their overall production. None of the largest conventional U.S. pork companies have yet committed to ending antibiotics overuse across all of their various brands of pork products. The companies that heed consumers’ call will have the market advantage.

When it comes to policy—on a federal level, the FDA should close a major loophole in their antibiotics policy that is still allowing routine antibiotic use to continue under the guise of “disease prevention” nationwide. In the meantime, state policymakers can help bridge the gap by following the lead of legislators in Maryland and California, who recently passed laws to restrict routine use of these antibiotics in livestock production within their own borders. And locally, cities can take a page from the Board of Supervisors of the City of San Francisco and require supermarkets to report information on the antibiotics used in the production of the poultry and meat products sold in their stores—and giving cities the opportunity to inform shoppers' choices.